I began watching Westworld recently to celebrate turning in my essay, and quickly got invested in it. The world, character arcs, and dynamism of the hosts intrigues me, especially as more of how the whole thing works slowly gets more developed and explained. Seeing how the show introduced its dynamics got me thinking about other sci-fi TV shows, and how they compare to movies of the same genre. The more I thought about it, the more I thought that sci-fi as a genre does much better in the realm of TV than film.

Why is that? Well, sci-fi often involves complex world/story-building when done right, and needs to be set out in a way that doesn’t seem rushed or boring. In film, there is only a two-two and a half hour span to introduce and develop the story and the world. Often times, that means there are aspects that are underdeveloped, rushed, or simply never explained. Which, when portrayed in a particular, more natural way, can work out.

Think of Mad Max: Fury Road. There wasn’t much actual explanation of the post-apocalyptic world, but there was visual representation, paired with just the right amount of explanation where the audience could understand how things worked. Of course, there were aspects left out; but the most important aspects are understood.

Now, the case of Mad Max is a case of sci-fi in films done well. More often than not, however, it takes a film multiple movies in order to explain itself and the world, sometimes dragging out stories that aren’t interesting enough or good past film 1 or 2. Or, in the case where there is only one film, the world is not explained enough, or simply isn’t interesting. Other times the story line is so bad and rushed that the world suffers as a result, too. In any sense, something is missing.

In the case of TV, however, there is a lot more to work with. Worlds can be properly flushed out and can work as an element of intrigue for the audience as it slowly unravels (in good shows, of course). Shows usually have a minimum of eight episodes to work out their world and dynamics, providing much more time and space to develop everything. The added fact that it usually comes out one episode a week even adds more to the suspense, maintaining greater interest than if it came out once every 2+ years. Sci-fi is a large and infinitely creative genre, and needs plenty of space to exist as a valid genre.

Sci-fi has had a long history in both film and movies, but is notably more prolific in TV, and much more recognizable. In the last decade particularly, sci-fi has been on the rise, after a period of falling behind fantasy. Sci-fi in TV shows also has the luxury of existing for longer, as average great shows can have as many as 9 or 10 seasons without appearing old or run-out, a heavy contrast from film. Shows can take on many more story arcs, as well, adding greater levels of complexity that otherwise couldn’t or wouldn’t exist.

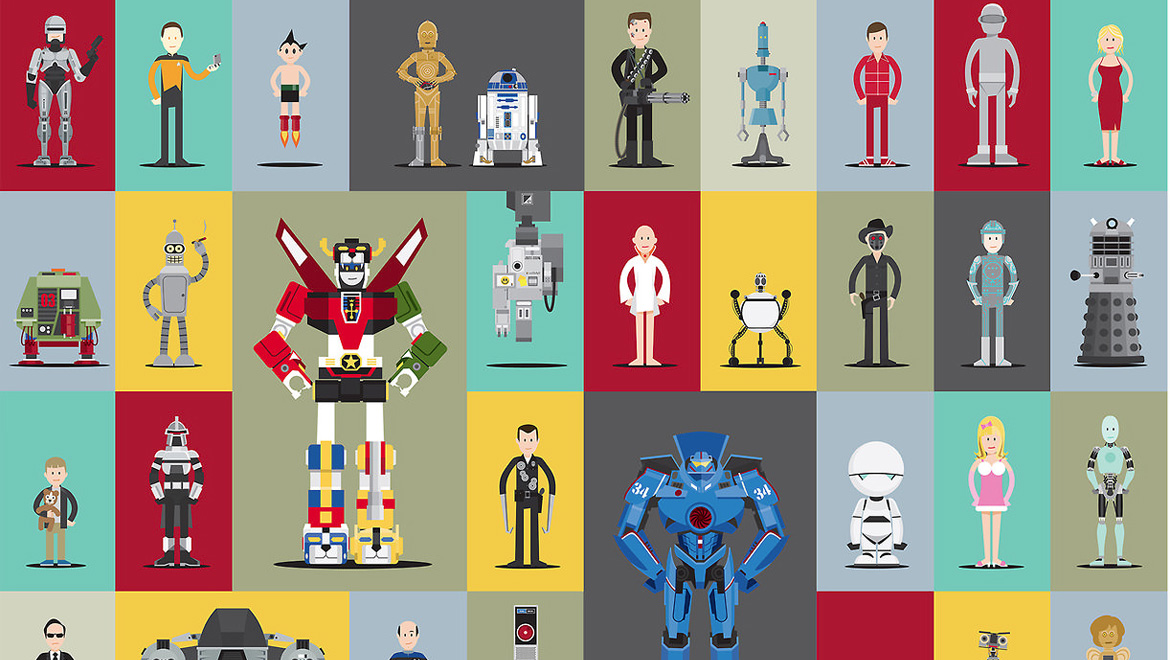

Sci-fi can exist in both film and television, and has phenomenal pieces in both sets of media (Star Wars, Star Trek, Stranger Things), paired alongside bad pieces. However, I tend to notice that TV overall has better sci-fi series than film, particularly in recent years, most likely as a result as the care and space provided through TV. TV has provided sci-fi a grander space, and has lent it greater popularity than film, causing the genre to have an overall better quality.